The reading of Sunday before last, from the Book of Revelation (Revelation 22:14-21).

“ ‘And, behold, I come quickly; and my reward is with me, to give every man according as his work shall be. I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last. Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city. For without are dogs, and sorcerers, and whoremongers, and murderers, and idolaters, and whosoever loveth and maketh a lie. I, Jesus, have sent mine angel to testify unto you these things in the churches. I am the root and the offspring of David, and the bright and morning star.’

“And the Spirit and the bride say, Come. And let him that heareth say, Come. And let him that is athirst come. And whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely. He which testifieth these things saith, Surely I come quickly. Amen. Even so, come, Lord Jesus. The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all. Amen.”

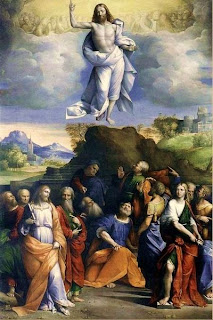

What a magnificent and beautiful close to the Christian scriptures, coming at the end of the last book of the New Testament. There were many other ‘revelations’ written by various people in the first few centuries of the Christian era, some of them as ancient as this one, and they are certainly worth reading and probably describe genuine visions of heaven, hell, and the Last Things. This, however, was the one Apocalypse that the church decided to include in the official canon, and they did so probably because of the tradition that it came from the pen of John the Apostle, and because it has the greatest power and scope of them all. It ranges from the angelic fall to the final redemption of the world, and that final redemption is what we see described here, in this excerpt which is read in Catholic and Anglican churches on the last Sunday of Easter this year.

As with the other excerpts from St. John’s Revelation, there is a lot that could be said about this passage. Every sentence is resonant and beautiful, and you can almost here the triumphal trumpet call between each verse, announcing the advent of the heavenly kingdom. Every sentence could provide us with spiritual food for meditation, for exegesis, for prayer, and for inspiration, and lots could be written about each verse. But I’m struck, first and foremost, by this sentence: “Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city.” It uses images that we’ve seen used often through the Book of Revelation: of the tree of life bearing twelve kinds of fruit, one for each month of the year, and of Heaven as a city with gates. John describes the gates of heaven earlier in the vision: “And the twelve gates were twelve pearls: every several gate was of one pearl,” giving us the phrase ‘pearly gates.’

The pearl, in Christian scripture and tradition, is symbolic of two things, knowledge and love, and inasmuch as these are two of the most basic attributes of God, and two of the most valuable things we are capable of, it’s a symbol of all things that are precious. Jesus tells us that the kingdom of heaven is like ‘one pearl of great price’ that a wise buyer would be willing to sell everything else he owns, in order to attain, and by comparing the gates to heaven to pearls, St. John is telling us how precious is the privilege- for it is a privilege, not a right- to enter through the gates of heaven.

But the pearl has another meaning too, and this meaning is clear to us when we consider what pearls are. Pearls are crystals largely of calcium carbonate- the same material that is the basic component of chalk, lime, and many mollusk shells- that form within the body of oysters when their soft flesh is irritated by a speck of dust or some other irritant. Obviously, oysters are sessile, stationary animals, filter feeders which can’t physically reach within their shells and pick out the dust speck, and can’t easily flush it out. They respond to irritants not by removing them but by isolating them: they deposit calcium carbonate layers, linked together by chitin and proteins, around the dust speck to make a smooth, sterile crystal surface that is no longer an irritant or a threat to their soft, vulnerable tissues. Out of the same common material that makes up chalk or clam shells, something of surpassing beauty and preciousness is born. Out of the pain and irritation caused to the oyster by a little grain of sand, is created something of dazzling beauty.

What a compelling symbol this is of the kingdom of heaven. For we are often asked, and we often ask ourselves, why evil must exist in this world, and why God allows it to exist. The answer is that for God to be perfect, there must be something outside him in order for him to relate to; evil must exist, specifically, so that God can bring good out of it. One example of this is that heaven could not truly be heaven if it had not been won through trial, through pain, and through suffering. Human virtues are largely defined in opposition to natural and physical evils: there could be no courage in this world if there were no dangers from war, disease, earthquake, or fire, there could be no virtue of charity if there were no one suffering in order to show charity to, and there could be no true sacrifice in a world without death, for as our Lord said, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man should give his life for his friends.” St. John talks in his Revelation of the crowned martyrs in the courts of God, who had demonstrated their faith by standing firm in the face of persecution, and of the Holy Innocents who enjoy a specially close relationship with Christ: “they followed the Lamb wherever he goeth.” These early Christian martyrs were crowned with glory through what they suffered, and the author of the Letter to the Hebrews tells us this was true of Christ as well: “And learned he obedience through the things which he suffered, and was made perfect.”

The irritation of the oyster’s tissues gives rise to the beauty of the pearl: similarly, the sufferings and afflictions that we experience in this life give us the occasion to triumph over evil and to show forth Christian virtues in our lives. Some of the best people I know, who most clearly exemplified the Christian virtues in their lives, were also some of the people who suffered some of the most painful personal tragedies. Yet in spite of all that they suffered they weren’t embittered or corrupted by it, but instead just grew deeper in the love that they showed to others. Their afflictions were the raw material from which God made saints, and made pearls of their lives and characters as bright as the pearls of heaven.

This life is the necessary preparation for heaven. This life is where we are tried, and found worthy or found wanting. There may be redemption in the next life, if we choose it- I believe there certainly is, and many saints and mystics through the history of the church have hinted that no one who truly desires salvation, in this life or the next, will truly be denied it. But whether we choose it, whether we desire it, is affected by what we make of our lives and souls here on earth. An existence lived entirely in heaven- without the experience to grow, to experience life in the material and physical world, to be tempted and overcome temptation, to suffer and overcome suffering- would be something less, and less perfect, than the prize of heaven won by struggle through the pains and afflictions of this life. We can’t go to heaven without living and dying first: as Christ tells us, “Unless a grain of wheat fall in the earth and dieth, it abideth alone; but if it dieth, it bringeth forth much fruit.”

Christ tells us, “Blessed are they that….may enter through the gates into the city.” Earlier, during his earthly ministry, he differentiated what it means to ‘enter through the gates’ from what it means to jump the fence or climb the walls: “He that entereth not by the door into the sheepfold, but by some other way, is a thief and a robber. But he that entereth in by the door is the shepherd of the sheep.” I’m always reminded, when thinking of the gates of heaven, of the image that the writer C. S. Lewis gives us in his children’s book, “The Magician’s Nephew.” Here he envisions the tree of life, in the paradisiacal garden of a new world, as a tree bearing golden apples giving life. An inscription on the gate of a garden states that whoever takes the fruit for himself, rather than for others, and who steals fruit rather than entering as bidden through the gate, will ‘find his heart’s desire, and find despair.”

This is what happens when we try to seize heaven for ourselves, or to create a simulated heaven here on earth, instead of trusting in God to bring us to the true heaven. Aldous Huxley, in his book ‘After Many a Summer’, satirizes one form of this desire to create an earthly heaven, the quest for eternal life: in the book, one character discovers the secret of long life, and manages to buy himself hundreds of years of life, but at the cost of losing his humanity and ‘maturing’ into a gibbering ape. Within history, we’ve seen the outcome of the capitalist attempt to build an earthly heaven of unlimited wealth and comfort, and the Bolshevik attempt to build an earthly heaven in which ‘innocence and virtue were compulsory’, and we have seen how such attempts are doomed to fail. The capitalist world succeeded in creating wealth and comfort on a scale never seen before in history, the Bolsheviks succeeded in creating a society beyond the profit motive, but sadly, both did so at a tremendous cost in human suffering and in the deformation of the human soul. We can and must strive to make this world as perfect as we can make it, but when we see perfection as something achievable in this life, we are tempted to break all kinds of moral laws as the price of getting there. The book of Revelation tells us that heaven is achievable only one way: after death, by the invitation of Christ to enter through the gates into the city. Whoever strives to jump over the wall, like Dante’s Ulysses who tried to take Purgatory by storm and ended up in hell, will ‘find his heart’s desire, and find despair.’

But let’s remember again, how trustworthy the promises of heaven are, and how sweet and gentle the invitation to us to enter through the gates. For this description of heaven is given to us by Christ Himself, “the Alpha and Omega, the Beginning and the End”, and the invitation to enter heaven is given us by “the Spirit and the Bride”, who tell us, “Come!” The Bride, here, is often taken to be the Church, but that’s unlikely: St. John has written a good portion of this book to address the church, and here he speaks of the Bride as separate from himself and from his audience. The Church is the bride of Christ, but she who is called ‘spouse of the Holy Spirit’ in a spiritual, not a carnal sense, is someone quite different: Mary, the Most Glorious Mother of God, the Queen of Heaven. Mary, and the Holy Spirit, ask us in the most intimate and gentle way, to come into the kingdom of heaven, and Christ promises us that whoever thirsts- no matter what their sins, no matter what their corruption, no matter what their lack of belief- are welcome to quench their thirst in the fountain of the water of life. We are told of the gates of heaven, that “they shall never be closed by day, and there shall be no night there”: i.e., once the victory of life over death and good over evil has be won, when ‘there shall be no [more] night”, the gates of heaven are open forever, to all. The call of the Spirit and the Bride is addressed not merely to those inside the city, but also to those outside the city, of whom Christ tells us are included, ‘sorcerers, and whoremongers….’. No one who truly craves repentance, and the mystical communion with God, will be denied it. Not now, not in the world beyond.

A long poem from early in the Christian era, attributed to St. Thomas, is called the Hymn of the Pearl, and it symbolizes the mystical quest for heaven and salvation as the quest of a young man who goes into Egypt in search of a precious pearl, is distracted and seduced from his quest, and falls into enjoying the earthly pleasures of Egypt. A letter is sent to him from “your father, the King of Kings, and your mother, the governor of the East” inviting him to turn from sin and pleasure and to seek out the pearl. The young man is awakened from the deep sleep into which he had fallen, he seizes the pearl and returns with it, casts off his old garments and is clad in new, clean robes, with which he ascends into heaven. The pearl here is symbolic of the kingdom of heaven, and the call that Christ gives us- here through the book of Revelation, through the other scriptures, through the various other religions and mystical experiences through which we apprehend and dimly perceive God, through the love of other people, through our reverence for nature- is to awaken from our ‘deep sleep’, to sharpen within us the thirst for eternal life, and to remind us that within the kingdom of heaven, there and only there, that thirst can finally be quenched by drinking of the waters of life, that water from which after we shall drink, we shall never thirst again.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit: as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen.